Scientists Prove That Rats Have High Levels Of Empathy With An Experiment

Rats. Most of us wouldn’t expect them to show a lot of… humanity. And yet, it turns out these furry little rodents are very social and have high levels of empathy. With a couple of exceptions, of course.

In 2011, scientists Inbal Ben-Ami Bartal, Jean Decety, and Peggy Mason came up with an interesting experiment to see just how much rats are willing to help out their fellow rodents.

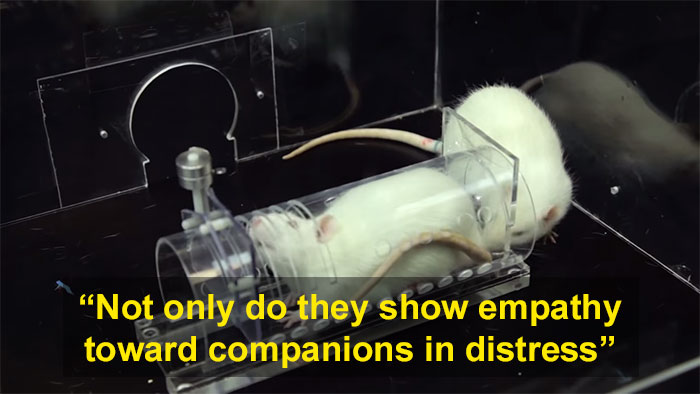

The results were (to put it mildly) awesome. Rats freed other rats who were in distress. What’s more, they even did so without the promise of a reward. And when presented with a choice between freeing a rat in trouble or opening up a container full of chocolate, they ‘liberated’ both and tended to share the chocolatey, chocolatey, spoils.

Scroll down for Bored Panda’s interview with Bartal who also caught us up on her other experiments regarding empathy in rats since then.

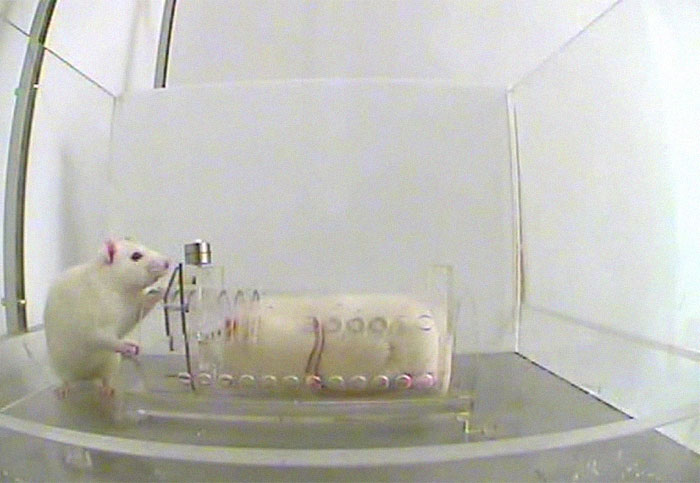

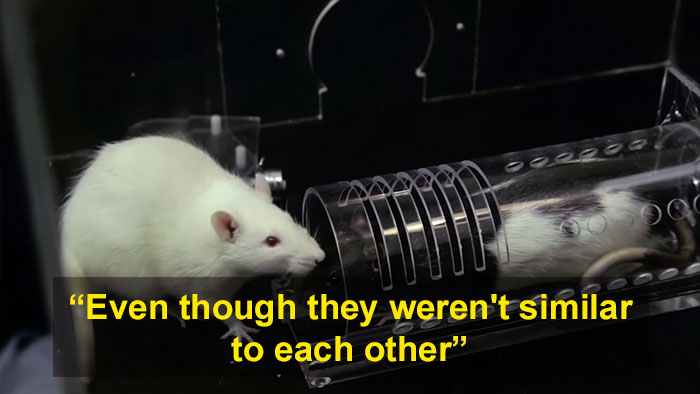

Scientists wanted to check if rats have a similar sense of empathy as humans do

Image credits: University of Chicago Medical Center

There are a couple of important caveats regarding empathy. In follow-up experiments, scientists determined that rats would only save other rats if they had socialized with an individual of that particular strain before. In other words, socializing breeds empathy and erodes dislike of differences and unfamiliarity. What’s more, scientists found that anti-anxiety medication erodes the level of empathy rats have for others of its kind.

Another group of scientists confirmed that rats care about their fellow rats more than about food. During the experiment, rats showed that they’ll gladly forego chocolate in order to help out a ‘drowning’ friend.

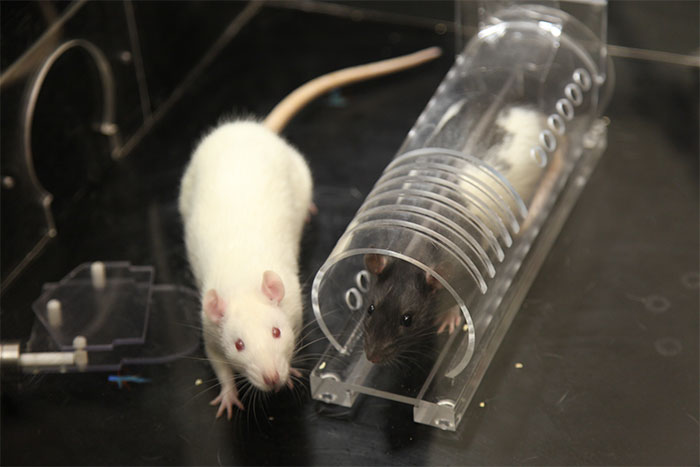

As it turns out, rats would help other rats in distress, even if there was no reward

Image credits: University of Chicago Medical Center

“Two relevant papers have come out for me since 2011. One in eLife shows that rats will help others of their ingroup (cagemates and strangers of the same strain) but not the outgroup (strangers of a black-furred strain they are not familiar with),” Bartal explained.

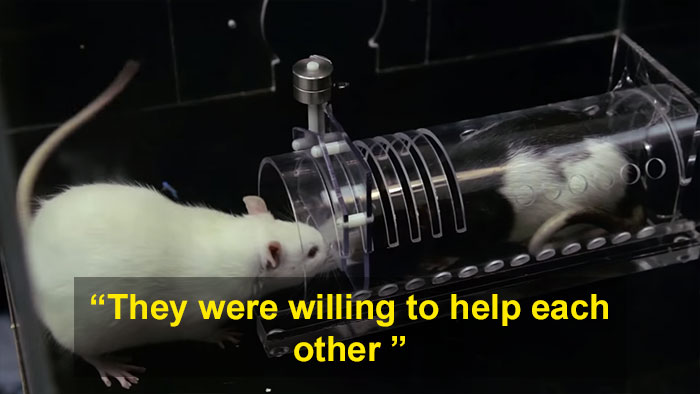

“So rats are selective in who they help. The encouraging thing is that we then found that cohabitation, living with a rat from the other strain for two weeks totally changes this behavior, and now rats will help that cagemate from the other strain. even more impressively, after living together for two weeks with one rat of the other strain, they will help strangers from the other strain as well.”

However, this doesn’t extend to all rats…

She continued: “Finally, rats were fostered at birth with rats from the other strain. Like Mowgli, they were raised with the other strain and never encountered their own kind. When they grew up, they only helped rats of the adoptive strain, not the biological strain. So in sum, social experience is what determines helping, not the genetic similarity.”

“We also show in another paper that helping depends on the transfer of distress between the two rats. Administration of a common anxiolytic (midazolam) reduces helping. Additionally, both rats show an increase in stress hormone corticosterone at the start of testing, but no stress response on the last day of testing for the pairs which learned how to open. non-helpers still show a stress response even on the last day, suggesting they were unable to learn how to open rather than not motivated,” the scientist told Bored Panda. “After that, I spent five years looking into the neural circuits of this behavior, hoping to publish soon.”

…rats need to have had social interaction with a particular ‘strain’ of rat to help them out

Bartal revealed to us that she just opened her very own laboratory at Tel-Aviv University and she is “Planning on continuing to study the brain’s way of processing distress in others, why we care about some and not others, and how the brain determines group membership. In rats first but hoping to look at humans as well.”

Which means that empathy stems from socializing with other, unfamiliar rats

“I am really interested in empathy across species, myself have not worked with others but lots of new papers coming out on empathy and sensitivity to emotions of others, as well as pro-social choices in birds, dogs, horses, even fish.”

Check out this video that goes into more detail about the follow-up experiment

Image credits: UChicago Medicine

According to Bartal, the discussion on empathy in animals gets “stuck on semantic issues.”

“For instance, the definition of empathy, how can we say that animals really feel empathy the same way we do. But empathy is a construct. We don’t even know what it is in humans really! I operate on the assumption that there is an evolutionary continuum between species, and that the basic building blocks of our responses are shared. Being sensitive to distress in others and motivated to care about their suffering is as old as the moment mother and child became connected for survival after birth.”

Here’s what some people thought of the research

No comments